Three scientists have won this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing innovative molecular structures capable of capturing vast quantities of gases — a breakthrough that could help remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and extract moisture from arid regions.

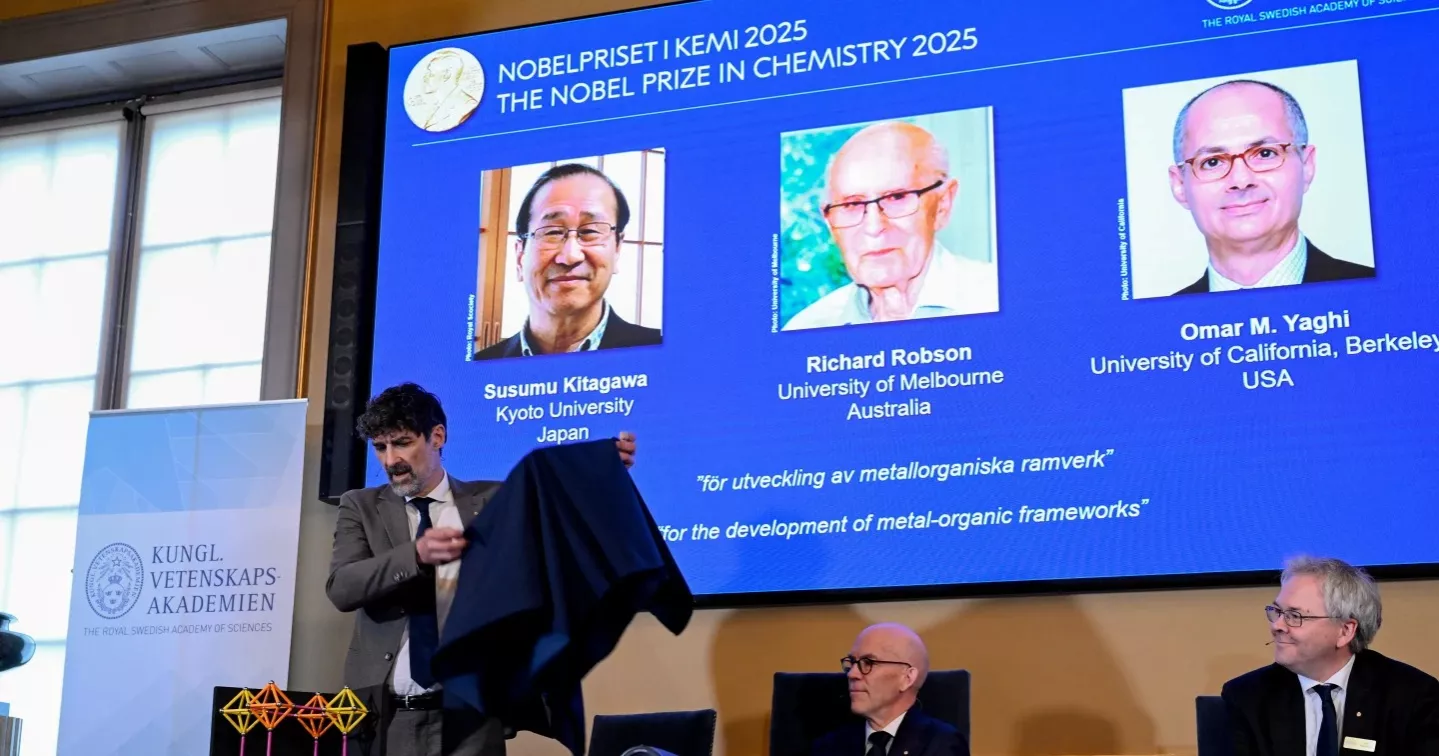

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the prize to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi for their pioneering work on metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) — intricate structures made from metal ions and organic linkers that can trap and store gases with remarkable efficiency.

The committee compared these molecular frameworks to Hermione Granger’s enchanted handbag in the Harry Potter series — seemingly small on the outside but capable of holding enormous volumes inside. The same principle applies to MOFs, which contain countless tiny cavities that can store large quantities of substances such as carbon dioxide or water vapor.

“These groundbreaking discoveries may contribute to solving some of humankind’s greatest challenges,” the Nobel committee said, citing their potential to combat pollution, tackle water scarcity, and advance medical applications.

Robson, 88, is affiliated with the University of Melbourne in Australia; Kitagawa, 74, is a professor at Kyoto University in Japan; and Yaghi, 60, works at the University of California, Berkeley.

A molecular breakthrough decades in the making

The three scientists worked independently but built upon one another’s discoveries over several decades, beginning with Robson’s foundational research in the 1980s.

Their efforts led to the creation of stable, porous structures with precisely engineered holes that allow gases or liquids to move in and out freely. These holes can be customized to capture specific molecules such as carbon dioxide, methane, or water.

“That level of control is quite rare in chemistry,” said Kim Jelfs, a computational chemist at Imperial College London. “It’s really efficient for storing gases.”

A small amount of the material can have an enormous internal surface area. According to Jelfs, just a few grams of these frameworks can offer as much surface space as a soccer field — ideal for trapping gas molecules.

“If you can store toxic gases,” said American Chemical Society President Dorothy Phillips, “it can help address global challenges.”

Applications and future potential

Researchers are now exploring how MOFs could be used to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, filter industrial pollutants, or harvest water from desert air to provide drinking water in dry regions.

Scientists are also investigating their use in targeted drug delivery, allowing medicines to be released gradually inside the body — an approach that could transform treatments for cancer and other chronic diseases.

“This could be really valuable across many industries,” said David Pugh, a chemist at King’s College London. However, he noted that practical challenges remain, as many of these structures currently work best under low-temperature, high-pressure conditions.

MOFs are already finding real-world uses, including in packaging materials that keep fruit fresh during long transport by slowly releasing ripening inhibitors.

The laureates’ reactions

Yaghi learned of his win while traveling from San Francisco to Brussels. Speaking at a news conference, he said, “You cannot prepare for a moment like that. The feeling is indescribable but absolutely thrilling.”

Kitagawa initially thought the call from Sweden was a telemarketing prank. “It was such a big prize, so I thought, ‘Is it really true?’” he said. When he realized it was genuine, he “felt relaxed and delighted.”

Robson, speaking from his home in Melbourne, said he was “very pleased, of course — and a bit stunned as well.” The 88-year-old added with a laugh, “This is a major thing to happen late in life when I’m not really in a condition to withstand it all, but here we are.”

Source: AP