Australian researchers have found that newly designed bite-resistant wetsuits can significantly reduce injuries from shark bites, offering surfers, divers and swimmers added protection in shark-prone waters.

Fatal shark attacks remain extremely rare worldwide. The International Shark Attack File at the Florida Museum of Natural History recorded fewer than 50 unprovoked shark bites on humans in 2024. Still, rising sightings of large sharks in several regions have prompted growing interest in protective gear.

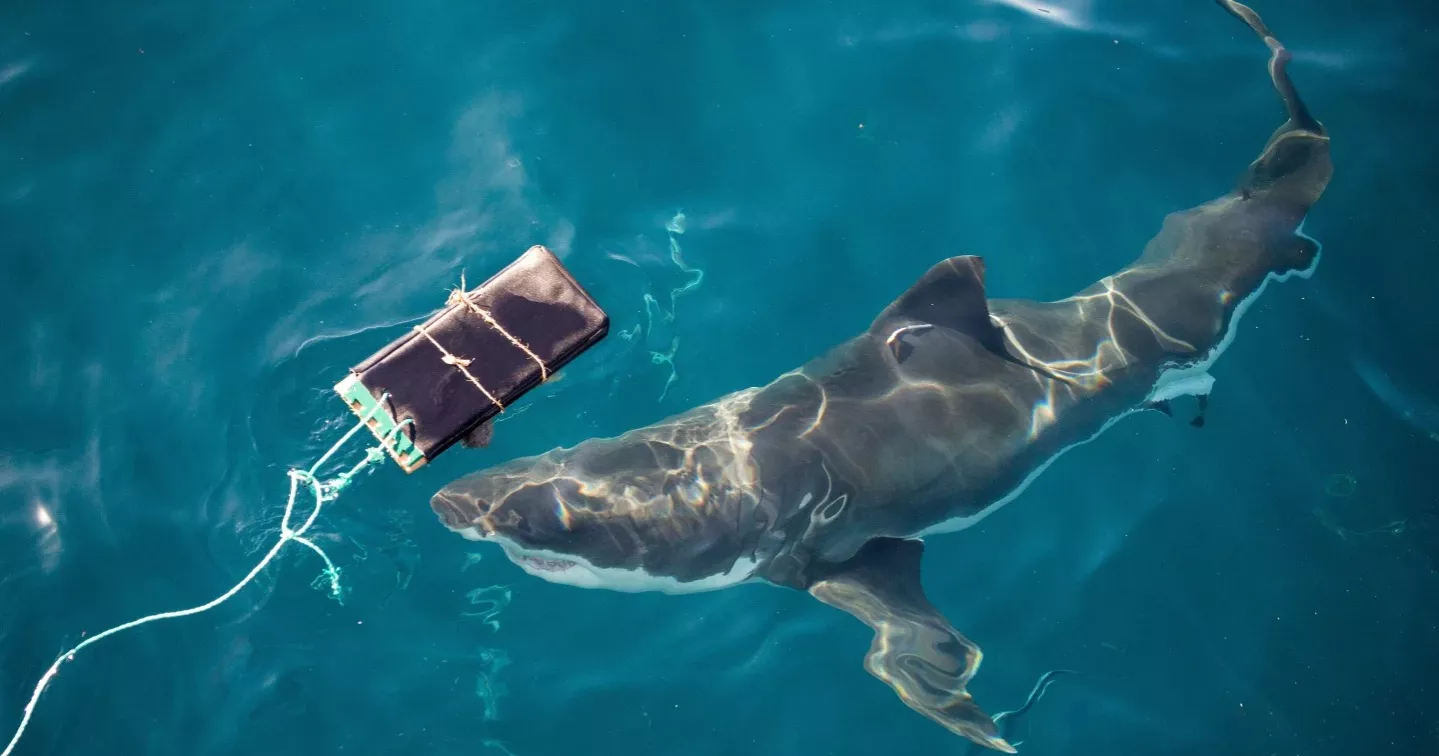

Scientists from Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia, tested four bite-resistant materials by exposing them directly to white and tiger sharks in the ocean. The results, published Thursday in the journal Wildlife Research, showed that all four materials were more effective than standard neoprene wetsuits in reducing damage.

“Bite-resistant materials do not prevent shark bites, but they can reduce injuries and be worn by surfers and divers,” said Flinders professor Charlie Huveneers of the Southern Shark Ecology Group, a co-author of the study.

The materials—Aqua Armour, Shark Stop, ActionTX-S and Brewster—were found to reduce substantial and critical damage that can often lead to severe blood loss, tissue destruction, or even limb loss. “All the materials reduced the extent of damage typically associated with severe hemorrhaging,” added researcher Tom Clarke, also a co-author.

While chainmail suits designed to resist shark bites have been around for decades, they lack the flexibility needed for aquatic activities such as surfing or diving. The new generation of wetsuits combines both protection and mobility.

The researchers emphasized that while these materials reduce the severity of injuries, bites from large sharks can still cause internal trauma and crushing injuries. Therefore, safety precautions in shark habitats remain essential.

The study has been welcomed by marine scientists elsewhere. “This is encouraging because it doesn’t rely on changing shark behavior,” said Nick Whitney, senior scientist at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life in Boston, who was not involved in the study. “In the rare event of a bite, these wetsuits may help you bleed less than if you were wearing a normal suit.”

The scientists stressed that the wetsuits are not foolproof but represent an important step in improving safety. “We hope this research will help the public make appropriate decisions about the suitability of using these products,” Huveneers said.