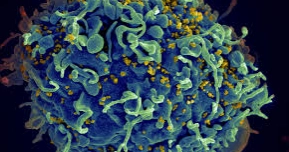

Decades of U.S.-led investment in global AIDS programs have significantly reduced deaths and provided life-saving treatment to vulnerable populations.

However, United Nations officials are warning that the abrupt loss of U.S. funding has created a “systemic shock” — one that could result in over 4 million AIDS-related deaths and 6 million new HIV infections by 2029 if alternative funding isn’t secured.

In a report released Thursday, UNAIDS said the withdrawal of U.S. support has already caused widespread disruptions: medicine supply chains have been broken, health facilities shuttered, testing and prevention efforts derailed, and frontline organizations forced to scale back or shut down operations.

There are growing fears that other donors may also retreat, threatening years of hard-won progress in HIV control. UNAIDS noted that global cooperation on health issues is under increasing strain due to conflicts, geopolitical changes, and climate pressures.

The crisis stems from a sudden policy shift earlier this year. In January, U.S. President Donald Trump suspended all foreign aid and began dismantling the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), effectively cancelling the $4 billion earmarked for HIV response in 2025.

Dr. Andrew Hill of the University of Liverpool said while Trump has the authority to redirect U.S. funds, the lack of advance notice left countries and clinics unprepared. “Patients were abandoned overnight,” he said.

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), launched in 2003 under President George W. Bush, has been a cornerstone of the global AIDS response. UNAIDS described it as a “lifeline,” having enabled testing for over 84 million people and treatment for more than 20 million. In Nigeria, for example, PEPFAR covered nearly 100% of the country’s HIV prevention drug budget.

In 2024, global AIDS-related deaths stood at about 630,000 — significantly down from the peak of 2 million in 2004 but unchanged since 2022.

Even before the funding cuts, HIV progress remained uneven. Half of all new infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and the majority of untreated individuals live in Africa and Asia, according to UNAIDS.

Doctors Without Borders’ Tom Ellman said some low-income countries are stepping up, but can’t possibly make up for the U.S. shortfall. “People will begin falling seriously ill within months,” he warned, “and we may see infections and deaths surge.”

Another major concern is the loss of HIV surveillance systems, which were largely U.S.-funded. Dr. Chris Beyrer of Duke University said that with no data, it will be “incredibly hard” to track or control the virus.

Meanwhile, promising advances like a new twice-yearly injection from Gilead — which has shown 100% effectiveness in preventing HIV — offer hope. The drug, known as Sunlenca, was recently approved by the U.S. FDA and hailed as a potential game-changer.

However, high costs may keep it out of reach for many countries. While Gilead agreed to allow generic production in 120 low-income nations, most of Latin America is excluded, despite rising infection rates there.

“We are at a point where ending AIDS is possible,” said Peter Maybarduk of Public Citizen. “But instead of pushing forward, the U.S. is pulling back.”