China’s long-term effort to challenge the global dominance of Boeing and Airbus with a homegrown commercial jet is facing mounting obstacles, with deliveries of its C919 aircraft expected to fall significantly below targets set for this year.

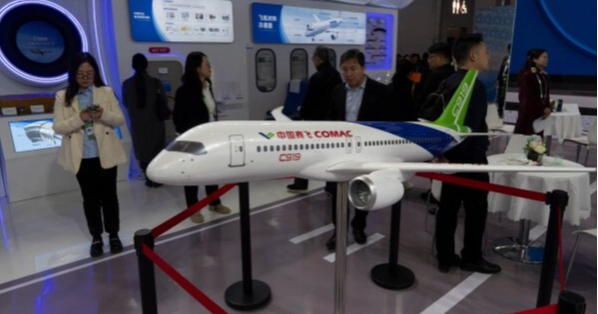

The C919, a single-aisle jet positioned to compete with Boeing’s 737 and Airbus’ A320, is developed by state-owned manufacturer COMAC. Beijing has held it up as a symbol of technological progress and growing self-reliance, despite the aircraft’s heavy use of Western components.

Ongoing trade tensions with the United States are threatening access to crucial parts needed for COMAC’s production plans, a program that has relied on extensive Chinese government funding.

“COMAC faces substantial risks in the current unpredictable policy climate, as its supply chain remains exposed to export controls and retaliatory measures between Washington and Beijing,” said Max J. Zenglein, Asia-Pacific senior economist at The Conference Board.

Analysts at Bank of America say the C919 program depends on 48 major U.S. suppliers such as GE, Honeywell and Collins Aerospace, along with 26 European and 14 Chinese firms. Trump has signaled potential new export curbs on “critical” software, following China’s tighter restrictions on rare earths.

“Existing choke points are increasingly being used as leverage between governments,” Zenglein noted. “This trend is likely to continue as strategic dependencies become political bargaining chips.”

The C919 completed its first commercial flight in 2023 and is expected to help meet huge domestic demand for new aircraft over the coming decades, with hopes of eventual international expansion across Southeast Asia, Africa and Europe.

According to aviation consultancy Cirium, COMAC delivered 13 C919s last year but only seven so far this year, falling behind plans to boost production and supply 30 jets in 2025. At present, only China’s three largest state-owned carriers — Air China, China Eastern and China Southern — are flying around 20 C919s in total.

Dan Taylor, head of consulting at IBA, said trade friction has “directly affected” delivery timelines. The U.S. suspension of export licenses for the aircraft’s LEAP-1C engines earlier this year, only reinstated in July, disrupted production plans, he added.

Trump vows extra 10% tariff on Canadian imports over Ontario ad dispute

The LEAP-1C engines, jointly built by GE Aerospace of the U.S. and France’s Safran, require U.S. export clearance, making the jet highly sensitive to political shifts.

“Reliance on Western engines and avionics continues to leave the program vulnerable to policy decisions outside COMAC’s control,” Taylor said.

Operational caution has also slowed progress, said Zenglein, noting that quality and safety priorities have contributed to the slower-than-expected production increase. Efforts to replace foreign parts remain complex, and China’s alternative engine, the CJ-1000A, is still undergoing tests, according to IBA.

Interest from foreign airlines including AirAsia has yet to translate into global operations due to the absence of U.S. and European certifications, which analysts say may take years.

For the C919 to become competitive worldwide, it will require strong economics, a reliable global support network and approvals from major safety regulators, said Richard Aboulafia of AeroDynamic Advisory.

China could require 9,570 new commercial aircraft between 2025 and 2044, Airbus forecasts, with single-aisle jets like the C919 making up the bulk of demand. Yet Airbus itself is ramping up its presence in China, adding a second A320 production line in 2026.

Trump halts Canada trade talks after Ontario’s anti-tariff ad

Analysts say breaking the Boeing-Airbus duopoly will take time. The C919 could expand its footprint within China and begin regional exports by the late 2020s, Taylor said. For now, limited certification and export control uncertainties are expected to continue restraining its international ambitions.

Source: AP