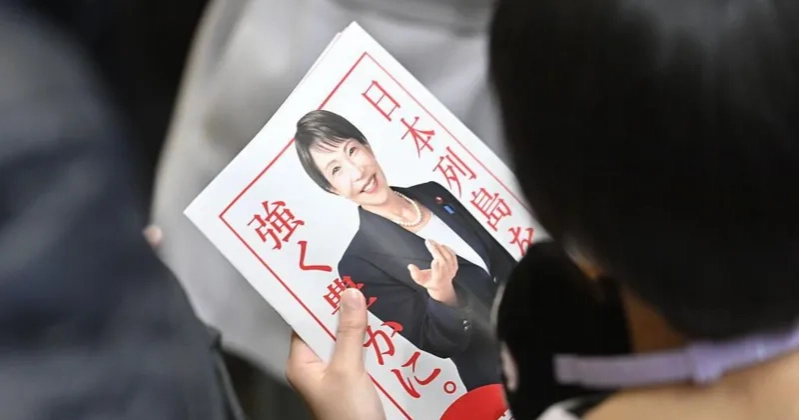

Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has emerged from a snap election with a commanding mandate, but the decisive victory now brings sharper focus on whether she can deliver the economic revival that has eluded the country for decades.

Takaichi and her Liberal Democratic Party won 316 of the 465 seats in parliament, giving her one of the strongest majorities seen in recent years in a country known for frequent changes of leadership. Supporters say the result gives her a rare opportunity to reshape policy in the world’s fourth-largest economy.

Japan’s challenges are deep-rooted. Economic growth has been sluggish for years, public debt is the highest in the world and the workforce is shrinking and ageing rapidly. Analysts say Takaichi now has political space to confront these issues, but expectations are high and risks are significant.

During the campaign, Takaichi pledged to prioritise growth over austerity, promising higher public spending, investment in strategic industries and tax cuts to boost household consumption. The approach marked a shift from her immediate predecessors and was closely watched by investors.

Financial markets reacted positively to her victory, with Japanese shares rising and what traders dubbed the “Takaichi trade” gaining momentum. Some investors bought equities while selling the yen and government bonds, although the currency later strengthened, a move seen by parts of the market as a sign of confidence.

However, concerns remain over how her plans will be financed. Government bond yields rose after she took office in October, raising alarms because Japan’s massive debt means even small increases in borrowing costs can have wide global effects. More spending combined with tax cuts would likely require additional borrowing, adding pressure to the bond market.

At the same time, the Bank of Japan is attempting to move away from decades of ultra-low interest rates as inflation picks up. Prices have risen sharply by Japanese standards, with staple items such as rice reportedly doubling in cost last year. The cost-of-living squeeze played a key role in voter dissatisfaction with the previous administration.

Some economists warn that expanding government spending could worsen inflation. They argue that tighter fiscal discipline and allowing interest rates to rise further would better stabilise prices and reassure investors. Others counter that cutting taxes may provide short-term relief to households feeling poorer.

Beyond financial policy, structural issues loom large. Japan’s population has been shrinking for years, creating labour shortages in sectors such as construction, care work, agriculture and hospitality. While immigration could help ease the strain, it remains politically sensitive and unpopular with parts of Takaichi’s conservative support base.

The prime minister has instead emphasised automation, technological innovation and greater participation by women and older people in the workforce. Economists caution that these measures alone may not be sufficient to sustain long-term growth without more foreign labour.

Japan’s external environment adds another layer of complexity. China, now larger in economic scale, is Japan’s biggest trading partner, making stable trade ties crucial while domestic demand recovers. Yet tensions with Beijing, including disputes over rare earth exports, have highlighted vulnerabilities in supply chains vital to industries such as electric vehicles and defence.

Takaichi has vowed to reduce Japan’s dependence on China in critical sectors while strengthening ties with the United States. She has endorsed higher defence spending and welcomed support from US President Donald Trump, signalling that the alliance with Washington remains central to her strategy.

Analysts say Japan cannot afford to fully align with one power against the other, arguing that balanced engagement with both the US and China is essential for economic resilience.

Observers note that Takaichi’s policy mix echoes that of her mentor, former prime minister Shinzo Abe, who combined aggressive stimulus with loose monetary policy. But the context has changed. Japan is older, competition in Asia is fiercer and global conditions are far less forgiving.

With a historic mandate in hand, Takaichi now faces the defining challenge of her leadership: translating political dominance into sustainable growth for an economy long stuck in low gear.

With inputs from BBC