China’s Communist Party

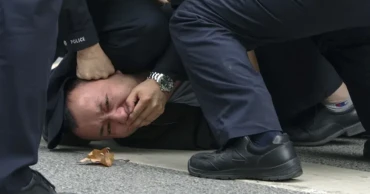

China security forces are well-prepared for quashing dissent

When it comes to ensuring the security of their regime, China’s Communist Party rulers don’t skimp.

The extent of that lavish spending was put on display when the boldest street protests in decades broke out in Beijing and other cities, driven by anger over rigid and seemingly unending restrictions to combat COVID-19.

The government has been preparing for such challenges for decades, installing the machinery needed to quash large-scale upheavals.

After an initially muted response, with security personnel using pepper spray and tear gas, police and paramilitary troops flooded city streets with jeeps, vans and armored cars in a massive show of force.

The officers fanned out, checking IDs and searching cellphones for photos, messages or banned apps that might show involvement in or even just sympathy for the protests.

An unknown number of people were detained and it’s unclear if any will face charges. Most protesters focused their anger on the “zero-COVID” policy that seeks to eradicate the virus through sweeping lockdowns, travel restrictions and relentless testing. But some called for the party and its leader Xi Jinping to step down, speech the party considers subversive and punishable by years in prison.

Read more: China’s protests are small but significant

While much smaller in scale, the protests were the most significant since the 1989 student-led pro-democracy movement centered on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square that the regime still views as its greatest existential crisis. With leaders and protesters at an impasse, the People’s Liberation Army crushed the demonstrations with tanks and troops, killing hundreds, possibly thousands.

After the Tiananmen crackdown, the party invested in the means to deal with unrest without resorting immediately to using deadly force.

During a wave of dissent by unemployed workers in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the authorities tested that approach, focusing on preventing organizers in different cities from linking up and arresting the leaders while letting rank-and-file protesters go largely untouched.

At times, they’ve been caught by surprise. In 1999, members of the Falun Gong meditation sect, whose membership came to rival the party’s in size, surrounded the leadership compound in Beijing in a show of defiance that then-leader Jiang Zemin took as a personal affront.

A harsh crackdown followed. Leaders were given heavy prison sentences and members were subject to harassment and sometimes sent to re-education centers.

The government responded with overwhelming force in 2008, when anti-government riots broke out in Tibet’s capital Lhasa and unrest swept through Tibetan regions in western China, authorities responded with overwhelming force.

The next year, a police crackdown on protests by members of the Uyghur Muslim minority in the capital of the northwestern Xinjiang region, Urumqi, led to bloody clashes in which at least 197 were killed, mostly Han Chinese civilians.

In both cases, forces fired into crowds, searched door-to-door and seized an unknown number of suspects who were either sentenced to heavy terms or simply not heard from again. Millions of people were interned in camps, placed under surveillance and forbidden from traveling.

China has been able to muster such resources thanks to a massive internal security budget that reportedly has tripled over the past decade, surpassing that for national defense. Xinjiang alone saw a ten-fold increase in domestic security spending during the early 2000s, according to Western estimates.

Read more: China’s Communist Party vows 'crackdown on hostile forces' as public tests Xi

The published figure for internal security exceeded the defense budget for the first time in 2010. By 2013, China stopped providing a breakdown. The U.S. think tank Jamestown Foundation estimated that internal security spending had already reached 113% of defense spending by 2016. Annual increases were about double those for national defense in percentage terms and both grew much faster than the economy.

There’s a less visible but equally intimidating, sprawling system in place to monitor online content for anti-government messages, unapproved news and images. Government censors work furiously to erase such items, while propaganda teams flood the net with pro-party messages.

Behind the repression is a legal system tailor-made to serve the one-party state. China is a nation ruled by law rather than governed by the rule of law. Laws are sufficiently malleable to put anyone targeted by the authorities behind bars on any number of vague charges.

Those range from simply “spreading rumors online,” tracked through postings on social media, to the all-encompassing “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” punishable by up to five years in prison.

Charges of “subverting state power” or “incitement to subvert state power” are often used, requiring little proof other than evidence the accused expressed a critical attitude toward the party-state. Those accused are usually denied the right to hire their own lawyers. Cases can take years to come to trial and almost always result in convictions.

In a further disincentive to rebel, people released from prison often face years of monitoring and harassment that can ruin careers and destroy families.

The massive spending and sprawling internal security network leaves China well prepared to crackdown on dissent. It also suggests “China’s internal situation is far less stable than the leadership would like the world to believe,” China politics expert Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation wrote on the Washington, D.C.-based conservative think tank’s website.

It’s unclear how sustainable it is, he said. “This could have the effect of either changing Chinese priorities or creating greater tensions among them.”

3 years ago

China’s Communist Party vows 'crackdown on hostile forces' as public tests Xi

China’s ruling Communist Party has vowed to “resolutely crack down on infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces,” following the largest street demonstrations in decades staged by citizens fed up with strict anti-virus restrictions.

The statement from the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission released late Tuesday comes amid a massive show of force by security services to deter a recurrence of the protests that broke out over the weekend in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and several other cities.

While it did not directly address the protests, the statement serves as a reminder of the party’s determination to enforce its rule.

Hundreds of SUVs, vans and armored vehicles with flashing lights were parked along city streets Wednesday while police and paramilitary forces conducted random ID checks and searched people’s mobile phones for photos, banned apps or other potential evidence that they had taken part in the demonstrations.

The number of people who have been detained at the demonstrations and in follow-up police actions is not known.

Also read: China lockdown protests pause as police flood city streets

The commission's statement, issued after an expanded session Monday presided over by its head Chen Wenqing, a member of the party's 24-member Politburo, said the meeting aimed to review the outcomes of October's 20th party congress.

At that event, Xi granted himself a third five-year term as secretary general, potentially making him China's leader for life, while stacking key bodies with loyalists and eliminating opposing voices.

“The meeting emphasized that political and legal organs must take effective measures to … resolutely safeguard national security and social stability," the statement said.

“We must resolutely crack down on infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces in accordance with the law, resolutely crack down on illegal and criminal acts that disrupt social order and effectively maintain overall social stability," it said.

Yet, less than a month after seemingly ensuring his political future and unrivaled dominance, Xi, who has signaled he favors regime stability above all, is facing his biggest public challenge yet.

He and the party have yet to directly address the unrest, which spread to college campuses and the semi-autonomous southern city of Hong Kong, as well as sparking sympathy protests abroad.

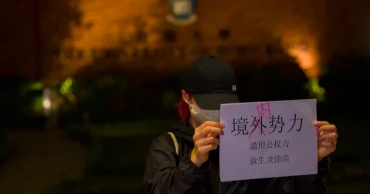

Most protesters focused their ire on the “zero-COVID" policy that has placed millions under lockdown and quarantine, limiting their access to food and medicine while ravaging the economy and severely restricting travel. Many mocked the government's ever-changing line of reasoning, as well as claims that “hostile outside foreign forces" were stirring the wave of anger.

Yet bolder voices called for greater freedom and democracy and for Xi, China's most powerful leader in decades, as well as the party he leads, to step down — speech considered subversive and punishable with lengthy prison terms. Some held up blank pieces of white paper to demonstrate their lack of free speech rights.

The weekend protests were sparked by anger over the deaths of at least 10 people in a fire on Nov. 24 in China’s far west that prompted angry questions online about whether firefighters or victims trying to escape were blocked by anti-virus controls.

Authorities eased some controls and announced a new push to vaccinate vulnerable groups after the demonstrations, but maintained they would stick to the “zero-COVID” strategy.

The party had already promised last month to reduce disruptions, but a spike in infections swiftly prompted party cadres under intense pressure to tighten controls in an effort to prevent outbreaks. The National Health Commission on Wednesday reported 37,612 cases detected over the previous 24 hours, while the death toll remained unchanged at 5,233.

Beijing’s Tsinghua University, where students protested over the weekend, and other schools in the capital and the southern province of Guangdong sent students home in an apparent attempt to defuse tensions. Chinese leaders are wary of universities, which have been hotbeds of activism including the Tiananmen protests.

Police appeared to be trying to keep their crackdown out of sight, possibly to avoid encouraging others by drawing attention to the scale of the protests. Videos and posts on Chinese social media about protests were deleted by the party’s vast online censorship apparatus.

“Zero-COVID” has helped keep case numbers lower than those of the United States and other major countries, but global health experts including the head of the World Health Organization increasingly say it is unsustainable. China dismissed the remarks as irresponsible.

Beijing needs to make its approach “very targeted” to reduce economic disruption, the head of the International Monetary Fund told The Associated Press in an interview Tuesday.

“We see the importance of moving away from massive lockdowns,” said IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva in Berlin. “So that targeting allows to contain the spread of COVID without significant economic costs.”

Economists and health experts, however, warn that Beijing can’t relax controls that keep most travelers out of China until tens of millions of older people are vaccinated. They say that means “zero-COVID” might not end for as much as another year.

On Wednesday, U.S. Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns said restrictions were, among other things, making it impossible for U.S. diplomats to meet with American prisoners being held in China, as is mandated by international treaty. Because of a lack of commercial airline routes into the country, the Embassy has to use monthly charter flights to move its personnel in and out.

“COVID is really dominating every aspect of life" in China, he said in an online discussion with the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

On the protests, Burns said the embassy was observing their progress and the government's response, but said, “We believe the Chinese people have a right to protest peacefully."

“They have a right to make their views known. They have a right to be heard. That’s a fundamental right around the world. It should be. And that right should not be hindered with, and it shouldn’t be interfered with," he said.

Burns also referenced instances of Chinese police harassing and detaining foreign reporters covering the protests.

“We support freedom of the press as well as freedom of speech," he said.

3 years ago

At 100, China’s Communist Party looks to cement its future

For China’s Communist Party, celebrating its 100th birthday on Thursday is not just about glorifying its past. It’s also about cementing its future and that of its leader, Chinese President Xi Jinping.

In the build-up to the July 1 anniversary, Xi and the party have exhorted its members and the nation to remember the early days of struggle in the hills of the inland city of Yan’an, where Mao Zedong established himself as party leader in the 1930s.

Dug into earthen cliffs, the primitive homes where Mao and his followers lived are now tourist sites for the party faithful and schoolteachers encouraged to spread the word. The cave-like rooms feel far removed from Beijing, the modern capital where national festivities are being held, and the skyscrapers of Shenzhen and other high-tech centers on the coast that are more readily associated with today’s China.

Read:India cranking up border infrastructure to narrow gap with China

Yet in marking its centenary, the Communist Party is using this past — selectively — to try to ensure its future and that of Xi, who may be eyeing, as Mao did, ruling for life.

“By linking the party to all of China’s accomplishments of the past century, and none of its failures, Xi is trying to bolster support for his vision, his right to lead the party and the party’s right to govern the country,” said Elizabeth Economy, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

This week’s celebrations focus on two distinct eras — the early struggles and recent achievements — glossing over the nearly three decades under Mao from the 1950s to 1970s, when mostly disastrous social and economic policies left millions dead and the country impoverished.

To that end, a spectacular outdoor gala attended by Xi in Beijing on Monday night relived the Long March of the 1930s — a retreat to Yan’an that has become of party lore — before moving on to singing men holding giant wrenches and women with bushels of wheat. But it also focused on the present, with representations of special forces climbing a mountain and medical workers battling COVID-19 in protective gear.

The party has long invoked its history to justify its right to rule, said Joseph Fewsmith, a professor of Chinese politics at Boston University.

Shoring up its legitimacy is critical since the party has run China single-handedly for more than 70 years — through the chaotic years under Mao, through the collapse of the Soviet Union and through the unexpected adoption of market-style reforms that over time have built an economic powerhouse, though millions remain in poverty.

Many Western policymakers and analysts believed that capitalism would transform China into a democracy as its people prospered, following the pattern of former dictatorships such as South Korea and Taiwan.

The Communist Party has confounded that thinking, taking a decisive turn against democracy when it cracked down on large-scale protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989 and quashing any challenges to single-party rule in the ensuing decades — most recently all but extinguishing dissent in Hong Kong after anti-government protests shook the city in 2019.

Read:China's comical picture 'The Last G-7' raps Japan's Fukushima water

Its leaders have learned the lesson of the Soviet Union, where the communists lost power after opening the door to pluralism, said Zhang Shiyi of the Institute of Party History and Literature.

Instead, China’s newfound wealth gave the party the means to build a high-speed rail network and other infrastructure to modernize at home and project power abroad with a strong military and a space program that has landed on the moon and Mars. China is still a middle-income country, but its very size makes it the world’s second-largest economy and puts it on a trajectory to rival the U.S. as a superpower.

In the meantime, it has doubled down on its repressive tactics, stamping out dissent from critics of its policies and pushing the assimilation of ethnic minorities seeking to preserve their customs and language in areas such as Tibet and the heavily Muslim Xinjiang region. While it is difficult to gauge public support for the party, it has likely been boosted at least in some quarters by China’s relative success at controlling the COVID-19 pandemic and its standing up to criticism from the United States and others.

“We have never been so confident about our future,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying told journalists on a recent trip to the party’s historic sites in Yan’an.

Tiananmen Square, where Mao proclaimed the founding of communist China in 1949, is no longer a home for student protesters with democratic dreams. On Thursday, the plaza in the center of Beijing will host the nation’s major celebration of party rule. While most details remain under wraps, authorities have said that Xi will give an important speech.

The anniversary marks a meeting of about a dozen people in Shanghai in 1921 that is considered the first congress of the Chinese Communist Party — though it actually started in late July. The festivities will likely convey the message that the party has brought China this far, and that it alone can lift the nation to greatness — arguing in essence that it must remain in power.

Xi also appears to be considering a third five-year term that would start in 2022, after the party scrapped term limits.

The centennial is at once a benchmark to measure how far the country has come and a moment for Xi and the party to move toward their goals for 2049, which would mark the 100th year of communist rule, said Alexander Huang, a professor at Tamkang University in Taiwan. By then, Xi has said, the aim is basic prosperity for the entire population and for China to be a global leader with national strength and international influence.

Read:Biden at NATO: Ready to talk China, Russia and soothe allies

“Whether they can achieve that goal is the biggest challenge for the Chinese leadership today,” he said, noting growing tensions with other countries, an aging population and a young generation that, as elsewhere, is rejecting the grueling rat race for the traditional markers of success.

Still, the party’s ability to evolve and rule for so long, albeit in part by suppressing dissent, suggests it may remain in control well into its second century. The party insists it has no intention of exporting its model to other countries, but if China continues to rise, it could well challenge the western democratic model that won the Cold War and has dominated the post-World War II era.

“In the United States, you only talk, talk, talk,” said Hua of the Foreign Ministry. “You try to win votes. But after four years, the other people can overthrow your policies. How can you ensure the people’s living standards, that their demands can be satisfied?”

4 years ago

Ramadan in China: Faithful dwindle under limits on religion

Tursunjan Mamat, a practicing Muslim in western China’s Xinjiang region, said he’s fasting for Ramadan but his daughters, ages 8 and 10, are not. Religious activity including fasting is not permitted for minors, he explained.

The 32-year-old ethnic Uyghur wasn’t complaining, at least not to a group of foreign journalists brought to his home outside the city of Aksu by government officials, who listened in on his responses. It seemed he was giving a matter-of-fact description of how religion is practiced under rules set by China’s Communist Party.

“My children know who our holy creator is, but I don’t give them detailed religious knowledge,” he said, speaking through a translator. “After they reach 18, they can receive religious education according to their own will.”

Also Read: "Xinjiang genocide" allegations against China unjustified: scholars

Under the weight of official policies, the future of Islam appears precarious in Xinjiang, a rugged realm of craggy snow-capped mountains and barren deserts bordering Central Asia. Outside observers say scores of mosques have been demolished, a charge Beijing denies, and locals say the number of worshippers is sinking.

A decade ago, 4,000 to 5,000 people attended Friday prayers at the Id Kah Mosque in the historic Silk Road city of Kashgar. Now only 800 to 900 do, said the mosque’s imam, Mamat Juma. He attributed the drop to a natural shift in values, not government policy, saying the younger generation wants to spend more time working than praying.

The Chinese government organized a five-day visit to Xinjiang in April for about a dozen foreign correspondents, part of an intense propaganda campaign to counter allegations of abuse. Officials repeatedly urged journalists to recount what they saw, not what China calls the lies of critical Western politicians and media.

Beijing says it protects freedom of religion, and citizens can practice their faith so long as they adhere to laws and regulations. In practice, any religious activity must be done in line with restrictions evident at almost every stop in Xinjiang — from a primary school where the headmaster said fasting wasn’t observed because of the “separation of religion and education,” to a cotton yarn factory where workers are banned from praying on site, even in their dormitory rooms.

“Within the factory grounds, it’s prohibited. But they can go home, or they can go to the mosque to pray,” said Li Qiang, the general manager of Aksu Huafu Textiles Co. “Dormitories are for the workers to rest. We want them to rest well so that they can maintain their health.”

By law, Chinese are allowed to follow Islam, Buddhism, Taoism, Roman Catholicism or non-denominational Protestantism. In practice, there are limits. Workers are free to fast, the factory manager said, but they are required to take care of their bodies. If children fast, it’s not good for their growth, said the Id Kah mosque’s imam.

Researchers at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a think tank, said in a report last year that mosques have been torn down or damaged in what they called the deliberate erasure of Uyghur and Islamic culture. They identified 170 destroyed mosques through satellite imagery, about 30% of a sample they examined.

The Chinese government rejects ASPI research, which also has included reports on Beijing’s efforts to influence politics in Australia and other Western democracies, as lies promoted by “anti-China forces.”

The government denies destroying mosques and allegations of mass incarcerations and forced labor that have strained China’s relations with Western governments. They say they have spent heavily on upgrading mosques, outfitting them with fans, flush toilets, computers and air conditioners.

Xinjiang’s biggest ethnic minority is Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim group who are 10 million of the region’s population of 25 million people. They have borne the brunt of a government crackdown that followed a series of riots, bombings, and knifings, although ethnic Kazakhs and others have been swept up as well.

The authorities obstruct independent reporting in the region, though such measures have recently eased somewhat. AP journalists visiting Xinjiang on their own in recent years have been followed by undercover officers, stopped, interrogated and forced to delete photos or videos.

Also Read: 'No Sweets': For Syrian refugees in Lebanon, a tough Ramadan

Id Kah Mosque, its pastel yellow facade overlooking a public square, is far from destroyed. Its imam toes the official line, and he spoke thankfully of the government largesse that has renovated the more than 500-year-old institution.

“There is no such thing as mosque demolition,” Juma said, other than some rundown mosques taken down for safety renovations. Kashgar has been largely spared mosque destruction, the Australian institute report said.

Juma added he was unaware of mosques being converted to other uses, although AP journalists saw one turned into a cafe and others padlocked shut during visits in 2018.

The tree-lined paths of the Id Kah Mosque’s grounds are tranquil, and it’s easy to miss the three surveillance cameras keeping watch over whoever comes in. The imam’s father and previous leader of the mosque was killed by extremists in 2014 for his pro-government stance.

About 50 people prayed before nightfall on a recent Monday evening, mostly elderly men. A Uyghur imam who fled China in 2012 called such scenes a staged show for visitors.

“They have a routine of making such a scene every time they need it,” said Ali Akbar Dumallah in a video interview from Turkey. “People know exactly what to do, how to lie, it’s not something new for them.”

Staged or not, it appears Islam is on the decline. The ban on religious education for minors means that the young aren’t gaining the knowledge they should, Dumallah said.

“The next generation will accept the Chinese mindset,” he said. “They’ll still be called Uyghurs, but their mindset and values will be gone.”

Officials say those who want to study Islam can do so after the age of 18 at a state-sponsored Islamic studies institute. At a newly-built campus on the outskirts of Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, hundreds train to become imams according to a government-authored curriculum, studying a textbook with sections like “Patriotism is a part of faith” and “be a Muslim who loves the motherland, abide by the national constitution, laws and regulations.”

“Continue the sinicization of Islam in our country,” the foreword reads. “Guide Islam to adapt to a socialist society.”

Though Islam lives on, the sinicization campaign has palpably reduced the role of religion in daily life.

Near Urumqi’s grand bazaar, several dozen elderly men trickled out of a mosque during an unannounced visit by an AP journalist. Prayers continue as usual, the imam said, though attendance has fallen considerably. A jumbo screen showing state media coverage of top Chinese leaders hung above the entrance.

Down the street, the exterior at the Great White Mosque had been shorn of the Muslim profession of faith. On a Wednesday evening at prayer time, the halls were nearly empty, and worshippers had to go through x-rays, metal detectors and face-scanning cameras to enter.

Also Read:China names Mars rover for traditional fire god

Freedom of religion in China is defined as the freedom to believe — or not believe. It was a mantra repeated by many who spoke to the foreign journalists: It’s not just that people have the right to fast or pray, they also have the right not to fast or pray.

“I really worry that the number of believers will decrease, but that shouldn’t be a reason to force them to pray here,” Juma said.

His mosque, which flies a Chinese national flag above its entrance, has been refurbished, but fewer and fewer people come.

4 years ago

Analysis: Biden faces a more confident China after US chaos

As a new U.S. president takes office, he faces a determined Chinese leadership that could be further emboldened by America’s troubles at home.

5 years ago

.jpg)