Asia

UN expert welcomes verdict on Nobel laureate Maria Ressa's tax evasion case

The UN expert on freedom of expression Thursday welcomed the decision by a Philippines' court to acquit journalist and Nobel laureate Maria Ressa and news outlet Rappler of tax evasion charges.

"The acquittal of Maria Ressa and Rappler is a victory for media freedom as well as justice," Irene Khan, UN special rapporteur on the freedom of expression and opinion, said.

"Journalistic work, especially journalistic expression about public and political issues, is an integral part of the right to freedom of expression and guaranteed by international human rights law."

Ressa and Rappler were charged by the former administration in the Philippines with evading tax payments after the news outlet raised foreign funding.

If convicted, the Nobel laureate would have faced up to 10 years imprisonment and fines. Maria and Rappler denied the charges and said the transactions involved legitimate financial mechanisms.

Noting that Maria Ressa continues to face several other charges, including cyber libel, Irene called on the authorities to withdraw all charges against her.

Read more: Nobel winner Maria Ressa, news outlet cleared of tax evasion

"I urge the government to abolish criminal libel, which has no place in a democracy," she said.

The special rapporteur has been in touch with the Pilipino government on this matter for several years.

Special rapporteurs are part of what is known as the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council.

Special Procedures, the largest body of independent experts in the UN Human Rights system, is the general name of the Council's independent fact-finding and monitoring mechanisms that address either specific country situations or thematic issues in all parts of the world.

Special Procedures' experts work voluntarily; they are not UN staff and do not receive a salary for their work. They are independent from any government or organization and serve in their individual capacity.

Read more: Journalist Maria Ressa reflects on Nobel Peace Prize win

Irene was appointed UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression on July 17, 2020. She is the first woman to hold this position since the establishment of the mandate in 1993.

3 years ago

Hong Kong to scrap isolation rule for new COVID-19 cases

Hong Kong will scrap its mandatory isolation rule for people infected with COVID-19 from Jan. 30 as part of its strategy to return the southern Chinese city to normalcy, the city's leader said on Thursday.

For most of the pandemic over the last three years, Hong Kong has aligned itself with China’s “zero-COVID” strategy, requiring those who tested positive to undergo quarantine. Many residents once had to be sent to hospitals or government-run quarantine facilities even when their symptoms were mild.

Currently, infected persons are allowed to isolate at home for a minimum of five days and can go out once they test negative for two consecutive days. After the rule is dropped, the mask mandate will be the only major COVID-19 restriction left in the city.

Read more: China halts visas for Japan, South Korea in COVID-19 spat

Chief Executive John Lee told lawmakers he made the decision based partly on the city's high vaccination and infection rates, saying the local community has a strong "immunity barrier.”

“As most infected persons only suffer mild symptoms, the government should shift from a clear-cut, mandatory approach to one that allows residents to make their own decisions and take their own responsibilities when we manage the pandemic,” he said.

He said it is a step all countries make on their paths to normalcy and that Hong Kong has reached this stage now, adding that the city's pandemic situation had not worsened after it started to reopen its border with mainland China about two weeks ago.

COVID-19 will be handled as another kind of upper respiratory disease, he said.

Edwin Tsui, the controller of the Centre for Health Protection, told a news conference that people with asymptomatic infections can go out freely or return to their workplace but infected students should not go to school until they obtain a negative test result. Those who suffer from COVID-19 symptoms should avoid leaving home, he said.

Residents will no longer need to report to the government when they test positive, he added.

Read more: China suspends social media accounts of over 1,000 critics of govt’s Covid-19 policies

Hong Kong's daily tally has fallen to 3,800 cases from 19,700 over the past two weeks. With many infected residents only having mild symptoms, most choose to isolate at home. The figures don’t include those who never report their cases but stay at home to avoid spreading the virus to others.

The city has one government-run facility in operation for those unsuitable for home quarantine, according to a government reply to a lawmaker's inquiries on Wednesday. But it did not elaborate on the facility's occupancy rate. The Associated Press has asked the government about such data.

Hong Kong, which once had some of the world's strictest COVID-19 rules, has been easing various restrictions to revive its economy, including removing an isolation rule for close contacts of those who tested positive for COVID-19 and vaccination requirements to enter certain venues.

3 years ago

India considering banning govt-identified ‘fake news’ on social media

The Indian government is considering blocking news it identifies as “false” on social media.

A draft proposal of new IT regulations revealed this week stated that the Indian government would not allow social media platforms to contain any content that it deems to be incorrect, according to NDTV.

This is only the most recent in a slew of actions taken by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration to control major tech companies.

Read more: UN Human Rights Council adopts 'fake news' resolution

Any information identified as “fake or fraudulent” by the Press Information Bureau (PIB), or by any other agency authorised for fact-checking by the government or “by its department in which such business is transacted”, would be prohibited according to the draft.

The government has also frequently engaged in disputes with different social media platforms when they disregarded requests for the removal of content or accounts that were allegedly propagating misinformation.

For spreading false information and endangering national security, the Indian government has blocked 104 YouTube channels, 45 videos, four Facebook accounts, three Instagram accounts, five Twitter handles and six websites

Read more: Instagram fact-check: Can a new flagging tool stop fake news?

Earlier in October, the government made the announcement that a panel would be set up to hear complaints from users about social media companies’ content moderation decisions. These businesses are already required to appoint internal grievance redress officers and executives to work with law enforcement officials.

3 years ago

Transgender men look for inclusion in conservative Pakistan

Aman, a 22-year-old transgender man from the eastern Pakistani city of Lahore, says he was always close to his father. When he was little and it was cold out, his father held his hands to warm them. When he was at university, his father would wait until he got home to eat dinner together, regardless of how late it was.

Now they are cut off. Aman's decision to live as a man has cost him everything. His parents and five siblings no longer speak to him. He dropped out of university and had to leave home. He has attempted suicide three times.

Trans men face deep isolation in Pakistan. The country, with a conservative Muslim majority, has entrenched beliefs on gender and sexuality, so trans people are often considered outcasts. But trans women have a degree of toleration because of cultural traditions. Trans women in public office, on news programs, in TV shows and films, even on the catwalk, have raised awareness about a marginalized and misunderstood community.

The Pakistani movie and Oscar contender “Joyland” caused an uproar last year for its depiction of a relationship between a married man and a trans woman, but it also shone a spotlight on the country’s transgender community.

Trans men, however, remain largely invisible, with little mobilization, support or resources. Trans women have growing activist networks — but, according to Aman and others, they rarely incorporate or deal with trans men and their difficulties.

“It’s the worst,” said Aman. “We are already disowned by our families and blood relatives, then the people we think are our people also exclude us.”

Trans women have been able to carve out their space in the culture because of the historic tradition of “khawaja sira,” originally a term for male eunuchs working in South Asia’s Mughal empire hundreds of years ago. Today, the term is generally associated with people who were born male and identify as female. Khawaja sira culture also has a traditional support system of “gurus,” prominent figures who lead others.

But there is no space within the term or the culture surrounding it for people who were born female and identify as male.

“Every khawaja sira is transgender, but not all transgenders are khawaja sira,” said Mani, a representative for the trans male community in Pakistan. “People have been aware of the khawaja sira community for a long time, but not of trans men.”

He set up a nonprofit group in 2018 because he saw nothing being done for trans men, their well-being or mental health.

Trans people have seen some progress in protecting their rights. Supreme Court rulings allow them to self-identify as a third gender, neither male nor female, and have underscored they have the same rights as all Pakistani citizens.

Although Mani was involved in the trans rights bill, most lobbying and advocacy work has been from transgender women since it became law.

“Nobody talks about trans men or how they are impacted by the act,” said Mani. "But this is not the right time to talk about this because of the campaign by religious extremists (to veto changes to the act). I don’t want to cause any harm to the community.”

Another reason for trans men’s low visibility is that females lead a more restricted life than males in Pakistan, with limits on what they can do, where they can go and how they can live. Family honor is tied to the behavior of women and girls, so they have less room to behave outside society’s norms. On a practical level, even if a girl wanted to meet trans people and get involved in the community, she wouldn’t be able to because she wouldn’t be allowed out, said Aman.

Coming from a privileged and educated family, Aman said his parents indulged him as a child, letting him behave in ways seen as male and dress in a boyish way. He wore a boy’s uniform to school.

But there came a time when he was expected to live and look like a girl. That meant fewer freedoms and the prospect of marriage. He didn’t want that life and knew there were operations to change his gender. But his father told him he was too young and would have to wait until he was 18, apparently hoping he would grow out of it.

Aman had nobody to speak to about his gender identity struggles. He used social media and search engines, making contact with a trans man in India who connected him with a WhatsApp group of trans men in Pakistan.

Aman grew his hair long and dressed like a girl “just to survive” while still at home, he said. He also felt he shouldn’t do anything to jeopardize the family’s honor.

“These restrictions created a war in my mind,” he said. “You have to socialize, and it was difficult for me because I had to socialize as a girl.”

He wasn’t allowed male friends because of the taboos around mixing with the opposite sex, nor was he allowed female friends because his parents feared it would lead to a lesbian relationship.

Still, Aman set goals to get educated, earn money and be independent, planning eventually to live as a man. By 2021, he was on hormone therapy and his voice was changing.

But it all changed when a family member asked outright if Aman was changing his gender. The question inflamed all the doubts and worries his parents already had about his steps to transition. They disowned him, saying he could no longer live under their roof if he wanted to live as a man.

“They said everything can be tolerated but we can’t tolerate this,” Aman said. His mother said it would hurt his siblings and their marital prospects. His sisters locked him in a bathroom once. Only his older brother supported him.

Aman moved out and began living alone – and fully as a man.

Mani has helped, giving him an office job at the non-governmental organization. Still, Aman barely gets by and faces constant problems. One is that he hasn’t changed his gender to male officially on his ID card, which he needs to vote, open a bank account, apply for jobs and access government benefits including health care.

He went once to NADRA, the government agency responsible for ID cards, but there the officials harassed him. They inspected him, talked derisively about him, and demanded a bribe. One official felt his chest.

He feels isolated.

“I’m satisfied with my gender, but I’m not happy to live anymore,” he said. “I love my family. I need my father, I need my brother.”

3 years ago

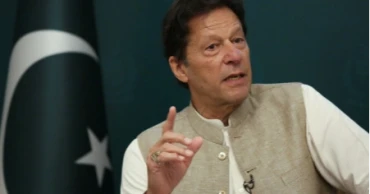

Imran Khan's party dissolves assembly in Pakistani province

The party of Pakistan's former Prime Minister Imran Khan on Wednesday dissolved a provincial assembly in the country’s northwest, where it held majority seats. Its rival, the ruling Pakistan Muslim League party, criticized the move, saying it meant to deepen the political crisis and force early parliamentary elections.

As opposition leader, Khan has been campaigning for early elections and has claimed — without providing evidence — that his ouster last April in a no-confidence vote in Parliament was illegal.

He has also accused his successor, Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif, the Pakistani military and the United States of orchestrating his ouster. Sharif, army officials and Washington have all dismissed the allegations.

Khan has also banked on his popularity and wide grassroot support to force early elections, and has since his ouster staged rallies across the country, calling for the vote. But Sharif and his Pakistan Muslim League have repeatedly dismissed the demands, saying elections will be held as scheduled — later in 2023 — when the current parliament completes its five-year term.

On Wednesday, Ghulam Ali, provincial governor in northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, dissolved the local assembly there, just days after another Khan ally, provincial lawmaker Pervez Elahi, dissolved the assembly in Punjab, the country’s most populous province, in eastern Pakistan.

Khan's Tehreek-e-Insaf party was in power in both provinces. The dissolution of the chambers will lead to snap elections in both Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab — and may lead to the party being reelected in both provinces — but will unlikely effect any change on the national level.

Read more: Ex-Pakistan PM Imran Khan wounded in firing at anti-govt rally

Sharif's government maintains that the tactics of the 70-year-old Khan are damaging the country's economy. Pakistan has struggled with the aftermath of unprecedented floods that devastated the country last summer and which experts say were exacerbated by climate change. Cash-strapped Pakistan is also facing a serious financial crisis and unabating militant violence.

Khan, a former cricket star turned Islamist politician, was wounded in a gun attack while leading a rally toward the capital, Islamabad, last November. One of Khan's supporters was killed and several others were wounded in the shooting.

Khan accused Sharif's government of being behind the attack; authorities have denied the allegation. The gunman was arrested on the scene.

Since the assassination attempt, Khan has been leading his political campaign from his hometown of Lahore, the capital of Punjab.

Read more: Imran Khan accuses Pak army of recreating 1971-like situation

Also on Wednesday, suspected militants ambushed a security convoy in a remote area in southwestern Pakistan, near the Iranian border, killing four soldiers, the military said. The army statement said the attackers used Iran's territory to launch the attack and that Islamabad has asked Tehran to arrest the assailants.

3 years ago

7.0 earthquake shakes east Indonesia

A strong earthquake shook eastern Indonesia on Wednesday, with no damage immediately reported and no tsunami warning issued.

Some residents tried to escape from houses after the magnitude 7.2 earthquake.

The U.S. Geological Survey said it occurred 60 kilometers (37.2 miles) deep under the sea, centered 150 kilometers (93.2 miles) northwest of Tobelo in North Maluku province.

No tsunami warning was issued by Indonesia’s Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center in Honolulu briefly said there was a potential threat to nearby Indonesian coasts but lifted the notice soon afterward.

Pius Ohoiwutun, a resident of Tobelo said that some people was running from houses when the quake shook.

“I felt a little swaying as the lamps also said. Some people tried to escape from their houses,” Ohoiwutun said on Wednesday.

A magnitude 6.1 quake also shook eastern Indonesia earlier Wednesday morning. No damage was reported.

Indonesia, a vast archipelago and a home of more than 270 million people, is frequently hit by earthquakes and volcanic eruptions because of its location on the “Ring of Fire,” an arc of seismic faults around the Pacific Basin.

A magnitude 5.6 earthquake on Nov. 21 killed at least 331 people in West Java. It was the deadliest in Indonesia since a 2018 quake and tsunami in Sulawesi killed about 4,340 people.

In 2004, an extremely powerful Indian Ocean quake set off a tsunami that killed more than 230,000 people in a dozen countries, most of them in Indonesia’s Aceh province.

3 years ago

Passenger's video captures last moments before Nepal crash

Airplane passenger Sonu Jaiswal’s 90-second smartphone video began with the aircraft approaching the runway by flying over buildings and green fields over Pokhara, a Nepalese city in the foothills of the Himalayas.

Everything looked normal as Jaiswal’s livestream on Facebook shifted from the picturesque views seen from the plane’s window to fellow passengers who were laughing. Finally, Jaiswal, wearing a yellow sweater, turned the camera to himself and smiled.

Then it happened.

The plane suddenly appeared to veer toward its left as Jaiswal’s smartphone briefly captured the cries of passengers. Within seconds the footage turned shaky and recorded the screeching sound of an engine. Toward the end of the video, huge flames and smoke took over the frame.

The Yeti Airlines flight from Kathmandu that plummeted into a gorge Sunday, killing all 72 on board, was co-piloted by Anju Khatiwada, who had pursued years of pilot training in the United States after her husband died in a 2006 plane crash while flying for the same airline. Her colleagues described her as a skilled pilot who was very motivated.

Read moreNepal begins national mourning after 68 killed in deadly plane crash

The deaths of Khatiwada, 44, and Jaiswal, 25, are part of a deadly pattern in Nepal, a country that has seen a series of air crashes over the years, in part due to difficult terrain, bad weather and aging fleets.

On Tuesday, authorities began returning some identified bodies to family members and said they were sending the ATR 72-500 aircraft’s data recorder to France for analysis to determine what caused the crash.

In India's Ghazipur city, nearly 430 kilometers (270 miles) south of the crash site in Nepal, Jaiswal's family was distraught and still waiting to identify his body. His father, Rajendra Prasad Jaiswal, had boarded a car to Kathmandu on Monday evening and was expected to reach Nepal's capital late Tuesday.

“It's a tough wait,” said Jaiswal's brother, Deepak Jaiswal.

The news of Jaiswal’s plane crashing in Pokhara reached his home barely minutes after the accident as news channels began broadcasting images of the aircraft's mangled wreckage, still burning and billowing thick gray smoke, Deepak said.

Read more: Families mourn Nepal plane victims, data box sent to France

Still, the family was not willing to trust the news, holding out hope for his survival.

By Sunday evening, however, it had become clear. Deepak, who confirmed the authenticity of Jaiswal's livestream to The Associated Press, was among the first in his family to watch the video that had since gone viral on the internet.

“We couldn't believe the news until we saw the video," he said. "It was painful.”

Jaiswal, a father of three children, worked at a local liquor store in Alawalpur Afga village in Uttar Pradesh state’s Ghazipur district. Deepak said his brother had gone to Kathmandu to visit Pashupatinath temple — a Hindu shrine dedicated to the god Shiva — and pray for a son, before setting off to Pokhara for sightseeing along with three other friends.

“He was not just my brother," Deepak said. “I have lost a friend in him.”

The tragedy was felt deeply in Nepal, where 53 passengers were locals.

Hundreds of relatives and friends of the victims consoled each other Tuesday at a hospital. Families of some victims whose bodies have been identified prepared funerals for their loved ones.

Co-pilot Khatiwada’s colleagues, however, were still in disbelief.

“She was a very good pilot and very experienced,” Yeti Airlines spokesperson Pemba Sherpa said of Khatiwada.

Khatiwada began flying for Yeti Airlines in 2010 — four years after her husband, Dipak Pokhrel, died in a crash. He was flying a DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 plane for the same airline when it crashed in Nepal’s Jumla district and burst into flames, killing all nine people on board. Khatiwada later remarried.

Sherpa said Khatiwada was a “skilled pilot” with a “friendly nature” and had risen to the rank of captain after flying thousands of hours since joining the airline.

“We have lost our best,” Sherpa said.

3 years ago

UN names Pakistani linked to Mumbai attacks as terrorist

The United Nations has designated an anti-India militant being held in Pakistan as a global terrorist, the world body’s second such designation stemming from the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai that killed 166 people.

The announcement regarding Pakistani citizen Abdul Rehan Makki was hailed by neighboring India on Tuesday, a day after the decision.

Pakistan's Foreign Ministry said the Islamic nation is itself a victim of terrorism and Pakistan supports counter-terrorism efforts at the international level, including at the United Nations.

Makki, 68, is a senior figure in the outlawed Lashkar-e-Taiba group, which is mainly active in the disputed Himalayan region of Kashmir. He was arrested in Pakistan's Punjab province in 2019 and convicted in November and December 2020 in two separate cases on charges of terror financing.

Makki was sentenced to one year in prison but officials say he is still in custody without providing an explanation. He is being held in Punjab pending his appeals, according to several government officials who are familiar with the case.

The U.N. Security Council committee overseeing sanctions against al-Qaida and Islamic State extremists and their associates put Makki on the sanctions blacklist after approval by the council’s 15 members.

Under the U.N. measure, Makki's assets can be frozen and he will also face a travel ban.

Makki is a close relative of Hafiz Saeed, a militant leader accused of orchestrating the Mumbai attacks. Saeed, 72, is serving a 31-year prison sentence and was designated a terrorist by the United States and the U.N. Security Council after the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

Saeed, like Makki, was never charged in connection with the Mumbai attacks that strained relations between Pakistan and India. He is the founder of Lashkar-e-Taiba, which was blamed by India for the attacks in India.

Read more: Savage Truth Behind Mumbai Carnage

Monday's U.N. Security Council decision came after China lifted a hold on adding Makki, who has been under U.S. sanctions since November 2010.

The spokesperson at India's Ministry of External Affairs in the capital New Delhi, Shri Arindam Bagchi, on Tuesday welcomed Makki's designation as a terrorist.

“India remains committed to pursuing a zero-tolerance approach to terrorism and will continue to press the international community to take credible, verifiable and irreversible action against terrorism," he said.

Mumtaz Zahra Baloch, the spokesperson at Pakistan's Foreign Ministry, said: “Pakistan is a victim of terrorism and supports counter-terrorism efforts at the international level including at the United Nations and other multilateral fora."

Baloch said in a statement that “Pakistan has always called for strict compliance with the Security Council’s listing rules, procedures and established processes to maintain the integrity of the UN counter-terrorism regime."

Since gaining independence from Britain in 1947, Pakistan and India, which have a history of bitter relations, have fought two of their three wars over Kashmir, which is split between them and claimed by both in its entirety.

Read more: 13th anniversary of Mumbai terror attacks observed in Bangladesh

3 years ago

Families mourn Nepal plane victims, data box sent to France

Nepalese authorities on Tuesday began returning to families the bodies of plane crash victims and were sending the aircraft's data recorder to France for analysis as they try to determine what caused the country's deadliest air accident in 30 years.

The flight plummeted into a gorge on Sunday while on approach to the newly opened Pokhara International Airport in the foothills of the Himalayas, killing at least 70 of the 72 people aboard. Searchers found the cockpit voice recorder and flight data recorder on Monday, and combed through debris scattered down the 300-meter-deep (984-foot-deep) ravine in search of the two missing, who are presumed dead. One body was found earlier Tuesday.

The voice recorder would be analyzed locally, but the flight data recorder would be sent to France, said Jagannath Niraula, spokesperson for Nepal’s Civil Aviation Authority. The aircraft’s manufacturer, ATR, is headquartered in Toulouse.

The French air accident investigations agency confirmed it is taking part in the investigation, and its representatives were already on site.

The twin-engine ATR 72-500t, operated by Nepal’s Yeti Airlines, was completing the 27-minute flight from the capital, Kathmandu, to the resort city of Pokhara, 200 kilometers (125 miles) west.

It’s still not clear what caused the crash, less than a minute’s flight from the airport in light wind and clear skies.

Aviation experts say it appears that the turboprop went into a stall at low altitude on approach to the airport, but it is not clear why.

Read more: Flight data, voice recorders retrieved from Nepal crash site

From a smartphone video shot from the ground seconds before the aircraft crashed, one can see the ATR 72 “nose high, high angle of attack, with wings at a very high bank angle, close to the ground,” said Bob Mann, an aviation analyst and consultant.

“Whether that was due to loss of power, or misjudging aircraft’s energy, direction or the approach profile, and attempting to modify energy or approach, that aircraft attitude would likely have resulted in an aerodynamic stall and rapid loss of altitude, when already close to the ground,” he said in an email.

The aircraft was carrying 68 passengers, including 15 foreign nationals and four crew members. The foreigners included five Indians, four Russians, two South Koreans, and one each from Ireland, Australia, Argentina and France. Pokhara is the gateway to the Annapurna Circuit, a popular hiking trail in the Himalayas.

On Tuesday afternoon, over 150 people gathered at Tulsi Ghat, a cremation ground on the banks of the Seti River in Pokhara, to mourn Tribhuwan Paudel, a 37-year-old journalist and editor at a local newspaper, who died in the crash. As a priest lit the funeral pyre, close friends of Paudel came together to reminisce.

Rishikanta Paudel said Paudel always celebrated his successes. “He would cry with happiness whenever I did something good ... I still feel like he might call me any time now and ask how I am."

Bimala Bhandari, the chairperson for the Federation of Nepali Journalists in Kaski district, described Paudel as driven and passionate about the development of Pokhara.

“He was dearest to all journalists here because of his nature,” said Badri Binod Pratik, a friend and journalist who taught Paudel. “The accident has taken him away from us ... I am crumbling since the day of the crash.”

Read more: Nepal begins national mourning after 68 killed in deadly plane crash

Funerals for other victims, many of whom were from the area, are expected in the coming days. They include a pharmaceutical marketing agent who was traveling to be with his sister as she gave birth, and a minister of a South Korean religious group who was going to visit the school he founded.

On Monday evening, hundreds of relatives and friends were still gathered outside a local hospital. Many consoled each other, while some shouted at officials to speed up the post mortems so they could take the bodies of their loved ones home for funerals.

Aviation expert Patrick Smith, who flies Boeing 757 and 767 aircraft and writes a column called “Ask the Pilot,” cautioned that a lot of details are still not known about the crash, but said that the plane “appears to have succumbed to a loss of control at low altitude.”

“One possibility is a botched response to an engine failure,” he told The Associated Press in an e-mail.

The man who shot the smartphone footage of the plane’s descent said it looked like a normal landing until the plane suddenly veered to the left.

“I saw that and I was shocked … I thought that today everything will be finished here after it crashes, I will also be dead,” said Diwas Bohora.

The type of plane involved, the ATR 72, has been used by airlines around the world for short regional flights since the late 1980s. Introduced by a French and Italian partnership, the aircraft model has been involved in several deadly accidents over the years. In Taiwan, two accidents involving ATR 72-500 and ATR 72-600 aircrafts in 2014 and 2015 led to the planes being grounded for a period.

Nepal, home to eight of the world’s 14 highest mountains including Mount Everest, has a history of air crashes. Sunday’s crash is Nepal’s deadliest since 1992, when all 167 people aboard a Pakistan International Airlines plane were killed when it plowed into a hill as it tried to land in Kathmandu.

Read more: 68 confirmed dead as passenger plane with 72 on board crashes near Pokhara airport

According to the Flight Safety Foundation’s Aviation Safety database, there have been 42 fatal plane crashes in Nepal since 1946.

The European Union has banned airlines from Nepal from flying into the 27-nation bloc since 2013, citing weak safety standards. In 2017, the International Civil Aviation Organization cited improvements in Nepal’s aviation sector, but the EU continues to demand administrative reforms.

3 years ago

China announces first population decline in recent years as births plunge

China has announced its first overall population decline in recent years amid an aging society and plunging birthrate.

The National Bureau of Statistics reported the country had 850,000 fewer people at the end of 2022 than over the previous year. It counts only the population of mainland China while excluding Hong Kong and Macao as well as foreign residents.

Read more: China's Communist Party capable of new, greater miracles

That left a total of 1.411.75 billion, with 9.56 million births against 10.41 million deaths, the bureau said at a briefing on Tuesday.

Men also continued to outnumber women by 722.06 million to 689.69 million, the bureau said, a result of the strict one-child policy that only officially ended in 2016 and a traditional preference for male offspring to carry on the family name.

Since abandoning the policy, China has sought to encourage families to have second or even third children, with little success. The expense of raising children in China's cities is often cited as a cause, reflecting attitudes in much of east Asia where birth rates have fallen precipitously.

China has long been the world's most populous nation, but is expected to soon be overtaken by India, if it has not already. Estimates put India's population at more than 1.4 billion and continuing to grow.

The last time China is believed to have recorded a population decline was during the Great Leap Forward at the end of the 1950s, Mao Zedong's disastrous drive for collective farming and industrialization that produced a massive famine killing tens of millions of people.

The bureau said Chinese of working-age between 16 and 59 totaled 875.56 million, accounting for 62.0% of the national population, while those aged 65 and older totaled 209.78 million, accounting for 14.9% of the total.

The statistics also showed increasing urbanization in a country that until recently had been largely rural. Over 2022, the permanent urban population increased by 6.46 million to reach 920.71 million, or 65.22%, while the rural population fell by 7.31 million.

Read more: China's economy grew 3% last year, not even half 2021

No direct comment was made on the possible effect on population figures of the COVID-19 outbreak that was first detected in the central Chinese city of Wuhan before spreading around the world. China has been accused by some specialists of underreporting deaths from the virus by blaming them on underlying conditions, but no estimates of the actual number have been published.

The United Nations estimated last year that the world’s population reached 8 billion on Nov. 15 and that India will replace China as the world’s most populous nation in 2023.

In a report released on World Population Day, the U.N. also said global population growth fell below 1% in 2020 for the first time since 1950.

Also Tuesday, the bureau released data showing China’s economic growth fell to its second-lowest level in at least four decades last year under pressure from anti-virus controls and a real estate slump.

The world’s No. 2 economy grew by 3% in 2022, less than half of the previous year’s 8.1%, the data showed.

That was the second-lowest annual rate since at least the 1970s after 2020, when growth fell to 2.4% at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, although activity is reviving after restrictions that kept millions of people at home and sparked protests were lifted.

3 years ago